Design patents have been making the news. Last summer, Apple’s $1.05 billion verdict against Samsung was famously based, in part, on the finding that Samsung infringed Apple’s rounded-rectangle and edge-to-edge glass designs. Since then, Yamaha, Thule, Oakley, Nike and Spanx, to name just a few, have litigated in the U.S. over the design of headphones, ski racks, sunglasses, footwear and women’s undergarments. And just last month, former head of the USPTO, David Kappos, published an OpEd piece describing design as “the new frontier of intellectual property.”

Nothing has fundamentally changed about the nature of design patents. The first US design patent was granted in 1842. The Statue of Liberty, Coke bottle, Volkswagen Beatle, Stealth Bomber and Star Wars’ Yoda are all protected by design patents. Design patents have long played an important role in consumer electronics, automotive, apparel, jewelry, packaging and other industries.

But industrial design is becoming increasingly important, Mr. Kappos explains, because the increasing functionality of man-made devices brings with it increasing complexity, so innovative companies are constantly seeking superior designs, a convergence of form and function that helps make the complex simple and sets their companies apart; and protecting such designs is critical.

While that explanation sounds reasonable, in China there are additional factors and – as always – the picture is complex and uncertain, but it is perfectly clear that companies doing business in China, from manufacturing to sales, should seriously consider the roles design patents can play with respect to brand protection, counterfeiting and unscrupulous business practices.

Explosion of Patents

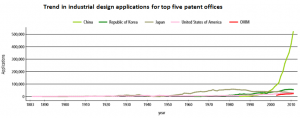

To start with, it should be noted that China grants far more design patents than any other jurisdiction. According to WIPO statistics, Japan’s Patent Office led the world in design patent applications from the 1950’s through the 1990’s; Korea’s Intellectual Property Office and the USPTO have shown a steady upward trend; but starting about 2000, the number of design applications filed in China has skyrocketed, so China’s Intellectual Property Office (SIPO) now issues more design patents than the next twenty offices combined and ten times the volume of the USPTO.

The vast majority of all design patents in China are granted to domestic applicants. Surely that is due, in part, to China’s indigenous innovation programs that provide cash bonuses and other financial incentives for the filing of patents and have been blamed for rewarding quantity at the expense of quality.

But perhaps there’s more to it than just that. More than one-third of all patent applications filed in China by domestic entities are for design patents, compared to just 10 percent for foreign applicants. Perhaps Chinese applicants have greater confidence than foreigners do that Chinese design patents, regardless of their quality or legitimacy, can give them an edge.

Applying for Design Patents

The scope of a design patent in China is essentially the same as in the U.S., where protection is allowed for any new, original, ornamental design for an article of manufacture.

China employs an absolute novelty standard, and includes no grace period, so prior use or publication anywhere in the world will render the design un-patentable. In theory, one may not patent a design that is merely an aggregate of two or more prior designs or design features and the design must be strictly ornamental, not functional, although courts sometimes appear to overlook those requirements. Unlike the U.S., graphical user interface (GUI) designs – one of the three design patents found to be infringed in the Apple/Samsung case – may not be protected by design patents in China.

However, the biggest difference between design patents in the U.S. and China is that in the U.S. design patens must pass a substantive examination, including a review of obviousness and prior art, but in China only a cursory examination is required, which looks into whether the application has been completed properly, drawings and power of attorney are attached, and the like.

The application must include either drawings or photographs of the design, along with a brief explanation used to interpret the drawings or photos and to indicate the essential portion of the design. Unlike the U.S. and other countries, in China the drawings may not include shading or broken lines to indicate non-essential features, so it may be prudent to eliminate non-essential features from the drawings to the extent possible.

Test for Infringement

The test for infringement in the U.S., as expressed by the Supreme Court and affirmed by the Federal Circuit in Egyptian Goddess v. Swisa, is whether an “ordinary observer” (as opposed to an expert) familiar with the prior art, would be deceived into thinking the accused design was the same as the patented design. The Federal Circuit has explained further, in Contessa Food Products v. Conagra, that the overall features of an accused product must be compared to the patented design as a whole, as depicted in all of the drawings.

China’s test is roughly equivalent. The courts inquire whether an “ordinary consumer,” familiar with the prior art and looking at the patented design as a whole, rather than focusing on minor differences, would find the two designs confusingly similar. Admittedly, even in the U.S. a fair amount of subjectivity is involved in determining when there is too much similarity – it’s more of an art than a science – but, in China the outcome seems especially uncertain.

In one case, Fiat sued the Great Wall Motor Company for producing a car that bore a striking resemblance to Fiat’s Chinese design patent. Fiat had already won a verdict against Great Wall in Italy, based on the same facts and an EU design patent, with the Italian court finding Great Wall essentially copied Fiat’s design and just substituted a different front end on its car. The Chinese courts found otherwise, ruling Great Wall did not infringe, due to minor differences that outweighed the general similarities.

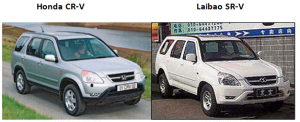

[Note: Several photos of accused designs and prior designs are shown below for reference. Of course, the proper test employed by the courts is a comparison of the accused product and the design patent drawings or photos.]

Similarly, in Honda v. The Patent Reexamination Board, the Supreme People’s Court examined a Chinese company’s SUV to decide if it infringed Honda’s design patent and found the ordinary consumer wouldn’t be confused by overall visual similarity due to minor differences between two designs. Although the Laibao SRV closely resembles Honda’s CR-V, the court found differences in the headlamps and side windows were sufficient to distinguish between the two designs.

On the other hand, when German bus-maker Neoplan sued a competitor for infringing its Chinese design patent, the Beijing court chose to disregard minor differences, finding infringement and awarding Neoplan over $3 million in damages, based on similarities between the two overall designs. Unfortunately for Neoplan, the defendant appealed the decision and then succeeded in invalidating the patent based on Neoplan having published the design in Germany prior to applying for the patent in China.

Is Enforcement Possible in China?

Some foreigners may be reluctant to patent their designs in China, because they fear the risks of bias, corruption and incompetence may render enforcement of their rights too uncertain, so the costs will likely exceed the benefits. Such fears are not wholly unjustified, but China’s legal system is improving rapidly and many foreign companies have successfully protected and enforced their intellectual property rights in China.

Motorola, Osram, Sony, Siemens, Kenwood, Bridgestone and Pfizer have all won patent lawsuits in China. In the design case described above, Neoplan won a $3 million verdict (though it was overturned on appeal). Apple is just one of many companies that have sought comprehensive design patent protection in China, including for the design of its stores (also protected by design patents in the U.S.).

While damage awards tend to be smaller across the board in China, infringement of a design patent could, in theory, result in a larger damage award in China, as in the U.S., because both countries allow for recovery of lost profits for infringement of a design patent; not just reasonable royalties. Injunctive relief may also be available and, unlike the U.S., in China one may enforce intellectual property rights through the courts or by filing a complaint with the local administrative office. Damages are unavailable through administrative enforcement, but an accused party may be fined and have the infringing goods seized. Of course, when seeking local administrative relief, it is especially critical to work with an experienced local lawyer, who knows not just the procedures but the people.

Finally, if you don’t register your designs in China there’s a good chance a Chinese company will and you may be forced to pay a toll for use of your own design. U.S., Japanese and Korean auto-makers have repeatedly accused Chinese companies of stealing their designs, only to find the accused patented the designs first in China, in some cases based on models being sold first by the accusers in the U.S. (before 2009, prior use outside of China did not conflict with China’s novelty requirement).

Or take the case of Volkswagen and its Chinese partner First Automobile Works (FAW). It was reported last year that VW was investigating whether FAW was preparing to use technology stolen from VW to manufacture its own-brand vehicles, which FAW intended to export to Russia. Or the incident with iPhone 5, when Apple was preparing to launch its product, but GooPhone, a notorious Hong Kong maker of knock-offs, claimed it had patented the design first and would sue Apple if it dared to sell the real thing in China.

These are the types of cases where foreign companies likely regret that they didn’t patent their designs early in China.

Conclusion

For the company that does business in China, manufacturing or selling products whose overall appearance or particular features have innovative designs that provide competitive advantage, it’s hard to imagine a reasonable justification for not seeking design patent protection.

Due to the absence of substantive examination, the application process is relatively cheap and fast. While the term of protection is just 10 years, amendments to China’s Patent Act are being considered that will likely increase the term to 15 years, to bring China into compliance with the Hague Agreement concerning International Registration of Industrial Designs (Hague Agreement).

It is generally prudent to patent not just the overall design for the entire product, but the designs of separate features and components, in order to protect against both cherry-picking infringers who seek to produce a hybrid design and companies that seek to copy only portions of the design in order to manufacture illegitimate spare parts.

Eventually it will be simple to obtain design protection worldwide pursuant to the terms of the Hague Agreement. The U.S. signed legislation last year that should come into effect about the end of 2013, to implement the Agreement. China will take longer, but they too will eventually implement the Agreement. When that time comes, it will be possible to obtain patent protection for up to 100 designs (in the same classification) in any jurisdiction that is a member of the Agreement, based on a single application and payment of the corresponding fees.

For now, until the Hague Agreement takes effect in China, one must file directly in China to protect ones design there. Make sure to file early, though, and keep the design confidential in the meantime, because China’s patent law requires absolute novelty and patent protection is only as strong as the patent.

———————

Please contact Asia Law if your require assistance with patents in Asia.